Intelligence as Pattern-Matching

Or, "the mind as a switch statement"

Epistemic status: wrote without doing any research in ~1h 1, purely based on personal observations, open to pushback!

Based on anecdotal evidence, it seems that intelligence, at least partially, is the ability to recognize patterns based on past experiences and apply them to new situations.2

In this context, a pattern can mean something concrete like an algorithm or a software implementation pattern or something more abstract like an economic principle or a philosophy concept.

And pattern-matching refers to “finding a close match” to the current situation / problem.

Though I do find the phrase pattern-matching more.

Let me give a few examples:

-

Doctors that have seen thousands of patients can diagnose new patients based on the similarity of the symptoms

-

Lawyers that have studied thousands of legal cases can come up with better strategies for the case they’re working on, by making use of insights from other case.

-

Software engineers don’t build new systems by reasoning from first principles — they pattern-match to find other similar systems and see how they were built, and what architectural design decisions can be applied to their system too. Even when there is no similar system, they fall back to commonly used software patterns and adapt them to their needs.

-

More generally, we make decisions everyday based on past experiences through pattern-matching.

In all the cases, it seems like the only information we have at our hand is our past experiences. By “thinking”, we aren’t creating new information (in a strict sense). We are just using ideas / concepts from our already existing knowledge-base to solve our current problem.

To be clear, by combining 2 ideas, you can come up with a novel insight and “generate” new knowledge; but what I mean is that you would not have come up with this novel insight if you did not already know the original 2 ideas.

Every idea is built on top of other ideas.

It’s different from rote-learning / memorization in the sense that the match doesn’t have to be exact (hence, “pattern”-matching). You’re never going to be in the exact same situation twice and you’re rarely going to be solving the exact same problem twice. So, you need to think more broadly, more abstractly and focus on past experiences with some similarity to the current problem while doing pattern-matching.

Note: Perhaps critical thinking is when you do pattern-matching at the most fundamental level — to identify which first-principles apply in this situation, and then work your way up by building on top of them (and them alone). But I know this is not convincing. So, maybe this can be seen as a separate component / dimension of intelligence altogether, as “first principles thinking”.

What factors affect how good someone is at pattern-matching?

In theory, one limiting factor is how many patterns a person knows. If you know 100 patterns, you can pattern-match against at most 100 patterns.

But in practice, the true limiting factor is how many patterns / concepts can a person remember. Again, I don’t think this is a memorization task. It’s a matter of HOW you manage to remember your experiences in terms of the key principles that you are trying to generalise to other situations. This is often done subconsciously but it can also be done consciously. (In fact, that’s the whole tenet behind Cognitive Flexibility Theory.)

Note that you don’t have to only learn from your own experiences — by reading, you can absorb other people’s experiences and come up with more principles / patterns for yourself.

The second factor affecting how good you are at pattern-matching is just how well you can spot similarities (aka how good your regex algorithm is).3

There are different levels at which you can perform pattern-matching:

-

trying to find a similar problem within the same domain

-

trying to apply a concept from another domain (e.g. applying economics to tech)

-

combining multiple partial matches to solve your problem (e.g. taking 2 big ideas from 2 different domains and combining them to solve your problem.)

If your pattern-matching algorithm is good at detecting even faint similarities (e.g. how sensitive it is), you’ll end up matching with more past experiences / lessons, and end with more principles to choose from.

It does not necessarily mean that all patterns you have in front of me will be relevant or useful for the task at hand — but at least you have the optionality of using it, which is better than not having it at all. In other words, you still need to figure out which one(s) are most relevant and can be applied in this context.

The bigger leaps you can take in terms of this pattern-matching, the more ground you can cover in the problem space. This means trying to maximize the amount of value you get from each thing you learn. It becomes useful to ask “What principles can I takeaway from this, that can be applied to future situations?”

Of course, if you generalize too much, the higher in terms of abstraction and scope, the more generic the principles and patterns tend to get. At that point, they might become mere platitudes and not useful.

So, it’s about being able to pattern-match at multiple layers of granularity / complexity, depending on the need. This is probably what makes people highly intelligent. Knowing when to cast how wide a net to prevent getting useless noise.

In a previous blog post, I wrote:

Imagine the space of all problems in the world. Now, imagine the problems you’ve encountered as being points located in this space. When you’re presented with a new problem, you’re probably going to start by trying to find a closely related problem that you’ve encountered before. So, if you’ve encountered and solved a lot of problems, it’ll be easier to solve related problems in the future because you are more likely to be able to find a close match (by spotting patterns, etc.) and then see if you can adapt the previous solution to this new problem. […]

The more ideas and concepts you have in your head, the easier it is for you to absorb new ones (because you can see how they fit in to your existing mental models by comparing them to other ideas). This is why people often say that knowledge compounds over time.

But that’s not all. If you want to have original ideas (which is much harder than being able to understand other people’s ideas), you need to have a dense space of points to begin with. The more ideas you have, the more you’ll be able to combine several of them together, and try to uncover insights.

Most original ideas are the amalgamation of existing ideas from different disciplines, applied in a novel way. And this is quite hard to do without enough points.

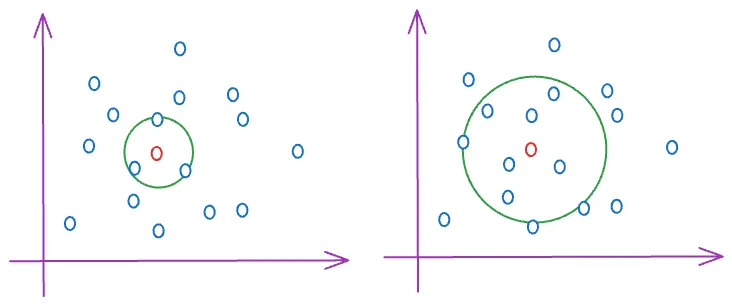

Here’s a visual representation of that too:

The blue points represent the existing patterns you have identified and internalized. The red point is the new problem you have encountered. In the left case, you have many more past patterns to rely on. In the right case, you only have one past pattern, which may or may not even be applicable.

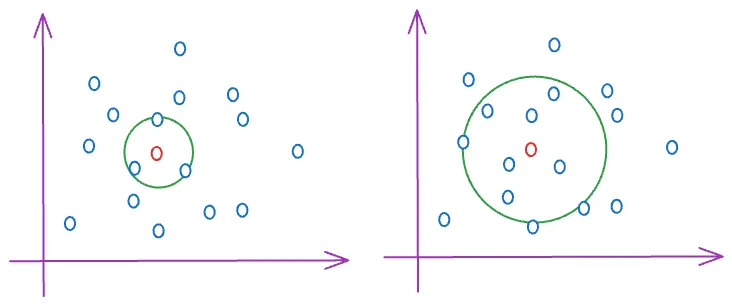

And on the importance of thinking laterally and across cross-domains:

The red point is the current problem you’re trying to solve and the blue points are the patterns you have gathered. If you can think more broadly (aka think laterally), think across domains, you can tap on more patterns / principles and use them too (maybe even combine them together). In the left case, you only have 3 points to play with, but in the right case, you have many more.

I finally understand what Charlie Munger meant when he said:

You’ve got to have models in your head, and you’ve got to array your experience — both vicarious and direct — onto this latticework of mental models.

We do this subconsciously all the time when we make any decision, and doing it consciously can probably accelerate the pace of building this latticework for ourselves.

As a final fun remark: this idea that intelligence is pattern-matching is itself an application of pattern-matching to itself, i.e., to find examples where people think in a pattern-matching way which is regarded as intelligence.

Footnotes

-

Actually I was in the middle of another post and was going off on a tangent — this tangent of pattern-matching — and I thought it made sense to just turn it into a standalone post and keep the other one distraction-free. ↩

-

About 50% through writing this post, I realized that this idea of “intelligence == pattern-matching” is essentially what “reasoning by analogy” is, and I kind of agree. So, I’m not saying anything new here, just explaining what I think of the idea in a different way — and I think framing it as pattern-matching makes it easier to understand, at least for me. (Ironically, this also means I was bad at doing the pattern-matching to spot this similarity between the two things much earlier on xD rip) ↩

-

I finally realized THIS is why IQ tests are all about spotting patterns in random sequences of shapes and it all makes sense now. ↩