Learning vs. Getting Things Done

Are LLMs actually slowing you down in the long-term?

At this point, LLMs like ChatGPT have become a household term and hundreds of millions of people use them on a daily basis.

AI as a Tool

It’s useful to think of LLMs as just tools. Like all tools, they increase the leverage you have. If you have a calculator, you can solve math problems faster than you would on a pen and paper. In the same way, if you have a certain skill X, you can use LLMs to improve your productivity / output related to the skill X by some factor (maybe 3x, 5x or even 10x).

The key thing to note here is that you still need to have the skills in the first place. 0 multiplied by any number is still going to be 0. If you don’t know whether a math problem requires addition or multiplication, you won’t be able to solve it even with a calculator.

You can magnify, but not replace, your skills with AI.

Two Modes

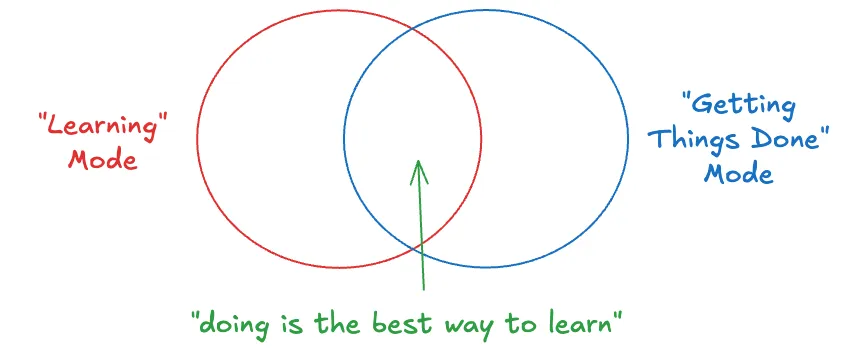

Broadly speaking, there are two kinds of modes you’re operating under: “learning” mode, and “getting things done” mode. And these modes are not mutually exclusive. In fact, one of the best ways to learn something is to just get your hands dirty and do it. The best way to learn how to code is to code. The best way to learn how to write is to write.

Other things in the “learning mode” set include reading books, watching videos, attending workshops. And before AI, probably the only other option in the “getting things done mode” was to hire someone else to do it.

That’s also why when assessing someone’s skills, it’s often very useful to look at the previous work of the person.

But now, with the prevalence of AI, this doesn’t hold true anymore. Because you can basically outsource your work to someone else (um, can we pretend this person’s name is “ChatGPT?”), and still claim (and truly believe) that you did it yourself.

The benefits of AI in getting things done are quite obvious, and indisputable. I’m personally a massive fan of these technologies myself, and it’s awesome to see the unprecedented pace at which they are evolving.

But I want to talk about the cost. The cost here is the sacrifice of the “learning” mode in favour of the “getting things done” mode. The cost is in choosing to favour the short-term temptations of quick victories and visible progress over the long-term benefits of deep knowledge. 1

Note that I’m using AI only as an example here (simply because it’s the most common manifestation of this problem), but the more general principle is that taking shortcuts to get things done quickly might actually be slowing you down in the long-term.

Costs

Firstly, as we said, doing X (yourself) helps you learn X better. What’s more, doing X is often even more important than getting X done, because this knowledge helps you solve other related problems in the future too.

Imagine the space of all problems in the world. Now, imagine the problems you’ve encountered as being points located in this space. When you’re presented with a new problem, you’re probably going to start by trying to find a closely related problem that you’ve encountered before, kind of like performing a nearest neighbour search of this problem. So, if you’ve encountered and solved a lot of problems, it’ll be easier to solve related problems in the future because you are more likely to be able to find a close match (by spotting patterns, etc.) and then see if you can adapt the previous solution to this new problem. This is how we most often solve problems — we don’t reinvent the wheel each time (i.e., we don’t always think from first principles), instead, we reason by analogy, try to use patterns and heuristics and apply them to the problems at hand.

Also, this is not just applicable to problems, but also to ideas in general. The more ideas and concepts you have in your head, the easier it is for you to absorb new ones (because you can see how they fit in to your existing mental models by comparing them to other ideas). This is why people often say that knowledge compounds over time.

But that’s not all. If you want to have original ideas (which is much harder than being able to understand other people’s ideas), you need to have a dense space of points to begin with. The more ideas you have, the more you’ll be able to combine several of them together, and try to uncover insights.

Most original ideas are the amalgamation of existing ideas from different disciplines, applied in a novel way. And this is quite hard to do without enough points. 2

So, by outsourcing a problem to AI, you’re depriving yourself of the chance to add this point to your space, which means it’s going to be more difficult for you to solve related problems when they arise. 3

Further, when you think deeply about a problem, you’re exercising your mental muscles. But when you ask an LLM to solve it for you, you aren’t. And if you don’t exercise your muscles enough, you aren’t going to be able to put them to use when you have to.

In the realm of ideas, you’re also reducing the likelihood of being able to think of something novel / new. Because this process of uncovering original insights by playing around with different ideas in your head is typically done without conscious effort. You don’t decide to sit down and try to combine ideas (well, you might, but I don’t think people do this). This happens when you’re working on something for a long time, and your mind wanders off in this space of ideas to find other points to help you find solutions for this problem (often when you’re showering or commuting). It’s a natural process that requires you to be actively involved and sunk deep into the problem.

(I think this happens most when you use LLMs to help you write — they follow your prompts too precisely, which means you never think of anything other than your first thoughts. Instead, if you write by yourself, you’re much more likely to spot inconsistencies while writing, add nuance, and improve the quality of your thoughts.)

Secondly, you can probably judge your own level of skill quite well. And by using AI to do the work or simply plagiarising, you know, deep down, that you aren’t developing any skill 4.

This applies particularly to students in schools and universities who are getting started in learning programming (or even writing for that matter), where the level of imposter syndrome is already quite high. Everyone thinks others are better and know so much more than them, but in reality nobody knows everything and everyone is learning things along the way.

One of the main causes for such imposter syndrome is that a big part of software engineering (when you’re getting started) is just searching, reading stack overflow and copy-pasting code. So, it doesn’t feel like you’re actually learning anything or have any valuable skills. You think even a trained monkey could probably do this. 5

AI makes this even more extreme. You literally all spend your time asking for help and trying to come up with the best ways to ask for help. You spend less than a few minutes on any one problem, and move on to the next without really understanding how it solved it. Naturally, you don’t think you’re improving, no matter what amazing output you show to the world (because you know that you didn’t come up with it).

As a learner, you should be in “learning” mode, not “getting things done” mode (sounds obvious right?). The point of learning is also to gain the confidence to tackle bigger / harder problems in the future, and also makes you more effective.

This may sound fluff, but it’s definitely not unimportant. A lack of confidence is a mental barrier to solving problems. If you don’t believe you can do it, you’re probably right.

You need the confidence when you’re doing something new, and you get that level of (real) confidence by having a proven track record to back it up. Confidence without any track record is simply naïveté.

So, gaining such confidence is like attaching turbo boosters to a car. It’s worth taking a few minutes to attach them if you’re going to be driving for hours.

Concretely, this means that you should be trying to improve your skills and achieve mastery as much as possible. More so than anything. Even if it means taking longer to do something. It’s better to optimise for confidence over productivity when you’re in learning mode.

This is probably a sufficient reason to avoid using AI to do your work when you’re getting started.

What Next

The key takeaway from this should be to prioritise true learning rather than just getting something done. How you achieve this is up to you — some people like to read books, just get started directly (recommended), watch videos — but the important part is making this active effort.

Ironically, you can use AI to help you learn better too (though you don’t have to!). I know, I know. It seems like I just spent so much time trying to convince you to not use AI. But that’s not true. What I was actually saying is that AI is just a tool and it’s up to you how you use it.

You have this choice between “learning” mode and “getting things done” mode every time you’re solving something.

It’s much more tempting to just get help to solve your problem, rather than get help to learn the concepts better.

But if you choose to, you can use AI to accelerate your learning at a faster pace than was ever possible before. You have a personalised tutor available 24/7 to help you understand better. All you have to do is ask. Instead of asking it to solve your problems, ask it to explain the concepts involved. And then have the self-discipline to actually try to achieve mastery of those concepts.

If you were in primary school learning basic arithmetic, and you had a calculator, you could do two things: 1) cheat using the calculator in the exam (assume it’s invisible so you won’t get caught), or 2) use the calculator as a personal grader and practise questions without relying on someone else.

Right now, each of us has this calculator. And if we use it right, we can develop our skills, deepen our understanding, and develop true knowledge, without depending on anyone else. If not, we’ll wind up completely dependent on the calculators, praying that the battery doesn’t run out, or that we don’t ever have to solve anything involving geometry / integration / (something that can’t be solved using a calculator).

The choice is ours.

Footnotes

-

I’m not claiming that “learning mode” is always better than “getting things done” mode. One simple counter-example would be for startups that need to “move fast and break things” to survive. But I do think most people naturally lean towards “getting things done” over “learning” (unless they’re making excuses to avoid getting the work done), so I want to tilt the scales back to where they’re more equal. ↩

-

If you have n ideas, you have O(n²) ways to mix 2 ideas, O(n³) ways to mix 3 ideas, and so on. If we agree that original ideas involve the marriage of 2 or more existing ideas, then you can have O(2^n) possibly original ideas with just n ideas. This is another pretty cool way to think about the compounding effect of knowledge. ↩

-

I don’t think this is necessarily bad, but it’s important to acknowledge that you’re prioritising “getting things done” over “learning”. In fact, this kind of just-in-time learning can actually be pretty effective for people who already have the confidence to say “i know i can figure this out along the way”. Of course, this also depends on the context. I wouldn’t want a pilot trying to learn the controls on-the-fly when the AI on his aeroplane stops working. ↩

-

Other than prompt engineering, which is very likely going to be obsolete in the next few years as AI models get better at generating higher quality output even with lower quality input, and AI researchers work on improving prompt tuning so that end-users don’t have to worry about writing the best prompts. ↩

-

But in reality, you’re doing a kind of literature review of things that have been done in the past, and you’re adding all that to your head so that you can tackle slightly different problems next. And as you get better, you can solve problems that are even more different than the ones you’ve seen (i.e., over time, you can make bigger leaps — in terms of euclidean distance — from one point to another, without any “stepping” points in the middle) ↩